An Analysis of John Ennis's Book, "Going Home to Geatland"

HH

Analysis of John Ennis's Book, "Going Home to Geatland"

Going Home to Geatland, a 2015 collection by John Ennis, serves as an intertextual synthesis of mythology, history and contemporary geopolitical conflict. Ennis utilises the framework of Old English epic (specifically Beowulf) and various global "hot zones", including Gaza, Afghanistan, Darfur, and Syria, to explore themes of dehumanisation, the cyclical nature of warfare, and the solitary mind’s confrontation with collective crisis. Given the current state of geopolitics a decade on, it's worth revising this book.

Overall, the book attempts an expansive scope that links the past to the present, often juxtaposing high culture (Shostakovich, Messiaen, Lorca) with the brutal realities of modern combat and systemic oppression. A significant portion of the text is dedicated to the Palestinian struggle, specifically the "Gaza Ground Zero" section. The book is dedicated to Yaron Caplan, "resisting the forces of de-humanisation."

Let's have a look at some of the core themes and philosophical framework.

Mythological Archetypes and "Geatland"

The title sequence uses the Beowulf narrative as a lens through which to view contemporary struggle, aging, and the seeming inevitability of confrontation. The Hero’s Return: Ennis employs Old English terminology to describe the hero’s internal and external battles. Key terms include Mearcstapa (wanderer along the borders), Hringsele (hall where spoils are dispensed), and Ece Raedas (eternal counsels). The Failure of Leadership: Figures like Hrothgar are depicted as "ultimately powerless" and "living in cloud cuckoo-land," allowing monsters to hold the centre stage while the nation suffers. The Persistent Dragon: The "dragon" represents the final, unavoidable conflict that must be faced "all over again" regardless of previous victories or the "gloss of victory" wearing off.

Geopolitical Crisis and Dehumanisation

Ennis provides a visceral examination of global suffering, focusing on specific individuals and localised tragedies to represent broader patterns of violence.

Gaza and Palestine: The section "Gaza Ground Zero" is an incisive critique of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, focusing on the human cost of the occupation. In Memoriam: Jihad Shehada al-Jaafari, a 19-year-old killed in 2015, serves as a central figure for this section. Ennis chronicles the "undying wail" of his mother and the blocking of ambulances by soldiers. The "Yoblands": Ennis uses this term to describe a culture of celebration surrounding destruction, where soldiers take "quickies" of dogs attacking children and social media users respond with "Likes" and "LOLs." Environmental Destruction: "Even the Olives are Bleeding" details the destruction of ancient orchards by settlers using chainsaws and bulldozers, highlighting a 3,000-year history being uprooted.

Afghanistan, Darfur, and Tibet. Moor Mahomed Taraki: The assassinated President of Afghanistan is memorialised in a poem that links the destruction of Kabul to global interests in gas pipelines. Ennis contrasts the billions spent on military destruction versus the World Bank’s reconstruction efforts. The Plight of Women: Here, Ennis highlights the extreme rates of female suicide in Herat and the kidnapping/rape of children (e.g., Sorava in Kunduz) under warlord rule.

Darfur: Described through the perspective of a deportee in "H-Block Khartoum," Ennis details torture with electric cables and the systemic failure of the UN and IMF to provide meaningful aid. Tibet: The poem for Kunchok Tsephel Gopey Tsang focuses on the "grinding torture" and the "forgotten prisons" in the "attic of the world."

Art as Resistance and Historical Witness

Ennis highlights the role of the artist in times of "barbarism," citing figures who maintained their integrity under totalitarianism or amidst war. Olivier Messiaen: Composing Abyss of the Birds in a field near Lille as a prisoner of Nazi war. Dmitri Shostakovich: Survives to "command that advancing infantry of double bases" while remaining "precarious in [his] own space" under Stalin. Federico García Lorca: Ennis reimagines Lorca’s final moments and his relationship with La Pasionaria, emphasising the "quick-limed cage of bones" that his death became.

Mastering the Lexicon of Geatland: A Guide to the Poetic Motifs of John Ennis

The Power of Archaic Language: Why Old English? In the poetry of John Ennis, the use of Old English, the alliteratively dense, consonant-heavy tongue of the Beowulf poet, functions not as a mere stylistic flourish, but as a linguistic palimpsest. By over-writing the modern landscape with archaic Germanic phonology, Ennis forces the reader to confront the "consonantal friction" of history; the ancient suffering of the Geats is revealed through the rubble of modern conflict. This "Geatland" framework provides the necessary grit to describe realities that modern euphemisms attempt to sanitise. Ennis adopts this framework for three primary reasons:

*Linking Mythology to History: By invoking the mearcstapa (the border-walker), Ennis suggests that the monsters of legend are identical to the "Grabbers" of modern geopolitics. Myth is not a fantasy of the past but a template for the present.

*The Solitary Mind and Collective Problems: The internal resolve of the hilderinc (fighter) reflects the broader societal struggle. The individual’s "weariness of heart" serves as a microcosm for a nation under siege.

*Bridging Past to Present: The cycle asserts that whether in the gleaming hall of Heorot or the "Gaza Ground Zero," the fundamental human experiences of fate, virtue, and the threat of obliteration remain unchanged across twenty centuries. This lexicon provides the structural "backbone" required to navigate a world where modern sonorities often fail to capture the visceral nature of survival.

The Landscape of Fear and Fate

Ennis synthesises environment and psyche through a grouping of terms that describe a narrative of crushing pressure and eventual departure.

*Atelic egesa (Soul-sapping fear): This is visualised as a "cold, marsh-like fog" rising to the belly. It is the atmosphere of being "tracked" and "obliterated," a fear so heavy it threatens to "stave in the chest like a heart attack."

*Helrunan (Hellish whisperers): These are the voices in the sulphur, those who wait in the shadows to profit from destruction, the "beneficiaries" of a hero's demise.

*To brimes farode (To the way of the wave): This signifies the final, solitary movement toward the sea after the "work is done and dusted," representing the ultimate departure of the individual.

Within this landscape, the concept of wyrd (fate) functions not merely as a death sentence, but as a "staying" force for the survivor. In the poem "Aet brimes nosan," fate provides a respite, an "Indian Summer" warmed by a "Zen garden", allowing individuals to endure even as the "flotsam and jetsam" of a working lifetime swirl around them.

Kings, Queens, and the Council of "Wise Men"

Social structures in the Geatland cycle serve as a vehicle for Ennis’s sharp critique of modern political "sonorities."

Snotera ceolras: Wise men in council; decoders of the future. Hringsele: The "hall of rings" or spoils, which Ennis transforms into a place of "collapsing rubble." In the poem Snotera ceolras, Ennis portrays these "wise men" as a "brave-arsed brigade" sitting round an oval table. They are ineffective decoders who offer nothing but "sonorous ramblings" and "fair words" while the individual "goes down." He critiques leaders like Hrothgar, described as a shadow of substance with "indigo gills," whose backbone has been "long filleted from him," leaving him to sway in the wind of his own delusions.

Virtue and Legacy: The Heroic Mindset

The survival of the individual depends upon internal virtues that Ennis compares against their real-world outcomes. These archaic terms provide the necessary "backbone" for understanding the weight of modern suffering. Ennis frames tragedies like "Gaza Ground Zero" and "Syria" not as ephemeral news cycles, but as recurring chapters in the human experience. The "filleted backbone" of a failing Hrothgar finds its modern echo in the "rubble" of cities where "flesh fries" and "kristallnacht for a kid" is enacted.

To master the lexicon of Geatland is to find the only language robust enough to name the "soul-sapping fear" that connects the ancient Geat to the modern survivor. In Ennis’s Gaza poems, social media serves as a tool for the dehumanisation of victims and the trivialisation of extreme violence, transforming atrocities into a voyeuristic digital spectacle. Ennis portrays it as a medium where ancient hatreds are performatively updated for a modern, often indifferent audience. Let's dig into this a little deeper.

It's worth alluding to the specific roles of social media highlighted such as:

Trivialisation and Entertainment: In the poem “Why Am I Smiling?”, Ennis describes soldiers taking a “quickie” video of their dog mauling a Palestinian child. This act is done for the “amusement of Facebook Friends,” with Ennis noting the chilling presence of “Likes” and “LOLs” from “smiling everyday tanned faces” watching the footage. This portrays social media as a space where human suffering becomes a source of casual entertainment.

Narcissism and Performance: In “To a Young Israeli Praying on his Tank in Gaza,” Ennis questions whether a soldier is praying not for spiritual reasons, but so the “TV camera will record his selfie” for the folks back home to see. Here, the act of war is reframed as a curated performance for personal or nationalistic validation.

The Contrast of "Texts": Ennis juxtaposes ancient, “resplendent texts” with modern “tweets”. By placing tweets alongside scriptures, he suggests that modern technology has become a new vessel for the same “myth-ridden minds” that have fuelled conflict for centuries, while also highlighting the brevity and superficiality of modern communication regarding life-and-death struggles.

Global Voyeurism: The poems refer to “shattered infants on our screens” as a routine occurrence. This implies that social media and digital broadcasting have made the visceral reality of Gaza a constant, yet often ignored, background noise in the lives of the global public.

By highlighting these digital interactions, Ennis critiques how social media platforms allow individuals to distance themselves from the moral weight of conflict, turning “human collateral” into digital content.

The fact that these poems were written over a decade ago is profoundly sad when one looks to what has been happening in Gaza since October 2023, when the Palestinian militant group Hamas led a surprise attack on Israel, in which 1,195 Israelis and foreign nationals were killed and 251 were taken hostage and Israel retaliated with such devastating and unrelenting force to that area. As always, the innocent, on all sides, continue to suffer at the hands of warmongers and evil regimens and this is much wider than Gaza as noted across the poems, which makes Ennis's book more important as a legacy statement.

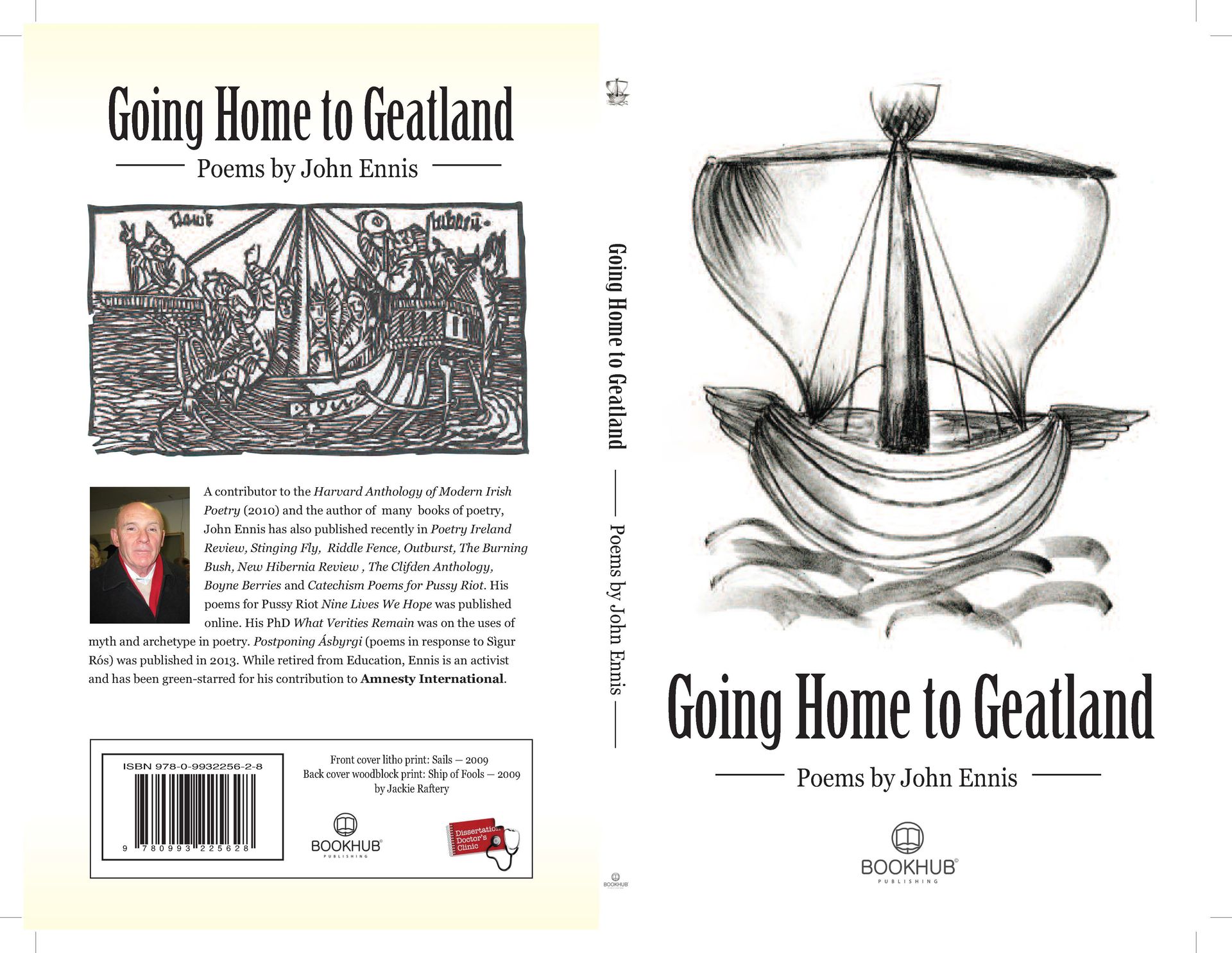

*Publisher: Book Hub Publishing. ISBN: 978-0-9932256-2-8.